The Remote Remembering Collection: (Inherited) Memories of Partition, Independence and Migration

This exhibition displays a collection of artwork, writing, songs and photographs that contributors associate with memories of Partition, Independence and migration. To continue our work on memories of Partition and migration during the Covid-19 pandemic and in collaboration with South Asian Heritage Month, we launched remote projects, such as ‘Memories of Independence’, the ‘Pakistan Memory Archive’ and ‘India at Home’, encouraging people to share with us the memories they have around the house and have inherited from family members. This collection is formed of the contributions we have received in response to these projects.

The collection speaks to (inherited) memories of British India, Partition, East and West Pakistan, Bangladeshi Independence and migration, highlighting the ways in which the past – through artwork, images, songs and writing – is still very much part of our present. It especially emphasises the significance of remembering the experiences and memories of these events today in the UK. The contributions reflect complex senses of belonging and the multifaceted identities of those from British South Asian backgrounds 73 years after independence from British colonialism.

This is a folding harmonium, made in Germany for export in the late 19th century. It was shipped to Karachi where it was bought from a music store for my grandmother, Inderjit. Just before Partition it was shipped to India along with her household goods. When I was 11, she gifted the harmonium to me. I have had it shipped to the UK and restored to musical health, but the foot pedals and the keys are all still the original materials. As is the beautiful walnut casing.

One interesting fact is that reed organs like this became co-opted into Indian music and the design eventually evolved into the floor or tabletop harmoniums which were more popular with Indian musicians as it fitted better with their group playing style, seated with other musicians.

Kavita A. Jindal, www.kavitajindal.com

“People were crushed to death. There were piles and piles of bodies”

“If we stayed where we lived all of us would have been killed”

“There was people everywhere. In front. Behind. Left and right. People as far as you can see”

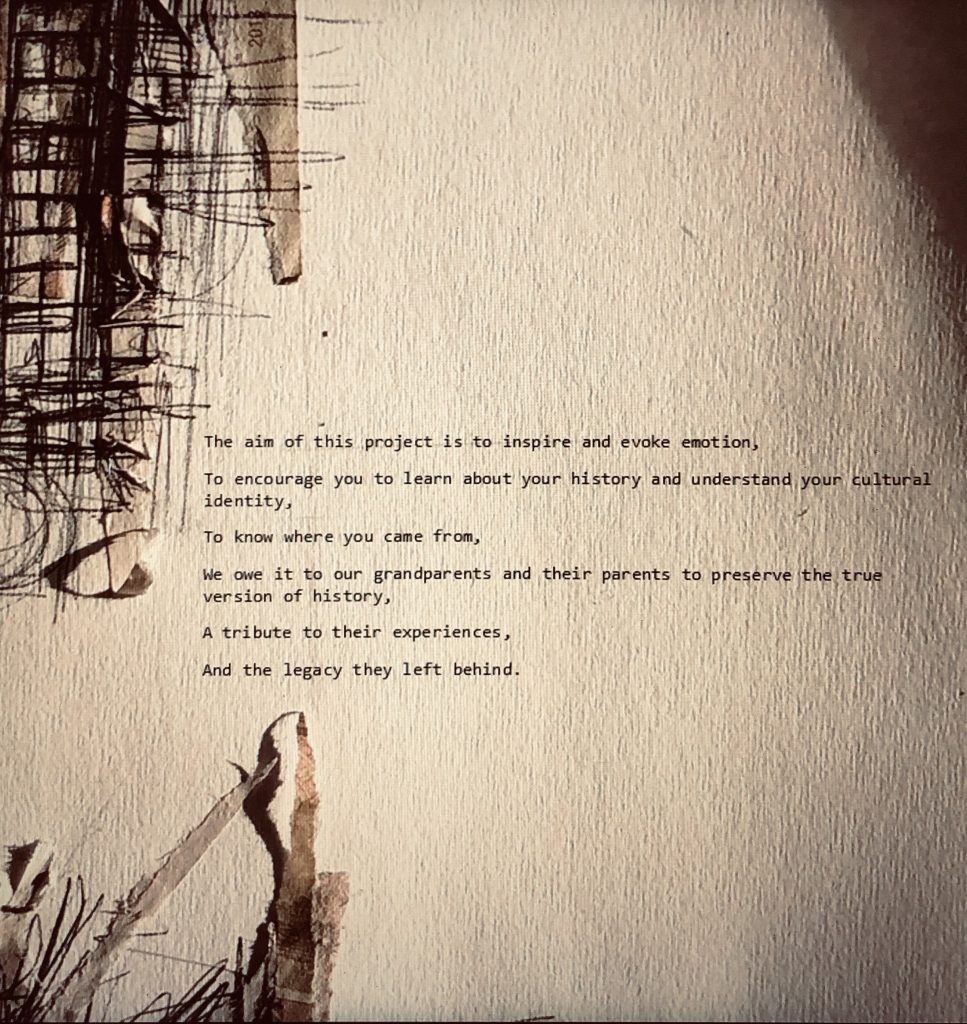

A project that combines Pre-Partition Pakistani architecture, family memories of Partition and mixed media.

In August 1947, centuries of conquest and oppression of the British Rule came to an abrupt end.

They split the states of Punjab and Bengal to create East and West Pakistan.

Over one million people were murdered and killed.

There were “blood trains” filled with passengers who had tried and failed to escape their homes having found themselves to be on the wrong side of the borders.

15 million people became refugees in their own home.

People that lived together as brothers and sisters side by side without conflict for generations.

So what changed?

People that ate the same food, shared the same language and culture were violently split apart.

Borders divided communities.

Families were torn apart.

Lines meant lives.

It was one of the deadliest communal massacres of the 20th century.

This is Partition.

“It’s written in history, people write with gold and silver words. This history was written with blood”

To see more from the Partition: Divide et impera project, see @maariah.art (Instagram)

The scenes of massacres witnessed by a seven-year-old girl.

“Look out, he is behind you –oh–no”. I curled my hands into my arms to stop myself shaking as I felt that fear rise in me. I was not terrified for myself, more for the woman who crumbled completely, her knees giving way, leaving her in a heap on the ground, as her baby is snatched away to be placed on the sharp edge of a long spear.

A young girl not more than ten, was savagely ripped apart with a knife by a group of five youths.

A mother was laying in the road dead, although I wasn’t certain, her baby still suckling on her breast. People slaughtered each other like soft vegetables with swords, axes, knives and anything they could lay their hands on.

“What are you doing”? I whispered as though they were listening to me. I felt sick to my stomach how a human can do such horrific acts to another human. I don’t know who was killing who; There were Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs, all chanting in their loud voices, Allah-hoo- Akbar, Her Her Mahndev and Joo boley so nihal Sat shree akal.

The blood was flowing, cut heads, limbs and half naked bodies of women were scattered all over the place. The ones who escaped were running towards the railway station. You have no idea how a little girl felt watching that horrible scene. I saw everything through barred windows of my house, facing the road, which took hundreds of people every day towards the railway station. We played games counting all the compartments of the train including people walking on the road to catch the train. That same window was now covered with iron rails, and we were banned from it, but unfortunately by accident I was there and wished I hadn’t.

The impact that had left on my young mind was so deep, I was ill for a month. This happened not twenty years ago, not forty, not even sixty years ago, it happened seventy-three years ago in a small town named Phagwara, in Punjab. I can still see myself standing behind that barred window, facing that terrible ordeal. The same people who once lived in harmony all their lives, sharing the same food, speaking the same language, taking part in each other’s happiness and sadness couldn’t even stop to think what they were now doing to each other. Their faces changed into demons. This was not between an ordinary Hindu, Muslim or Sikh; it was between the power-hungry leaders to gain the status they wanted to attain, no matter how many innocent lives were destroyed, and how much blood had to flow.

Every year on Independence Day it brings back the memories of that horrible day. Whilst we salute those who have fought and so many lives were sacrificed to gain independence, we should also remember with all our hearts the innocent people who had lost everything during partition too. I am sure people like me, have seen or experienced the trauma of these cruel, massacres, arson, forced conversions and savage sexual violence, must have prayed for it not to be repeated. They must also tell the younger generation of all their experiences. I also want to add something I have read somewhere. There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.“

Saroj Suri

10th August 2020

This contribution to the collection consists of a contributor’s father’s memories of British India, Partition and Independence, East Pakistan, the Bangladesh Liberation War and migration. Songs that the contributor’s father remembers listening to are placed between each memory.

“Originally from Sunamgonj (previously part of Sylhet, north Bangladesh), Dad is the second youngest of 7 brothers. He was born in March 1932. His father was an Iman and his mother was a housewife. It was a mixed Muslim/Hindu area and there were no issues. Dad said people lived side by side with no problems. In certain seasons, the house would be surrounded by water. Everyone knows Sunamgonj is land of water (flooding is regular occurrence) and we also have the Surma River that goes through this district.”

‘Gari Cholena Cholena’, Abdul Karim (Romesh Thakur version)

Pre-partition memories:

“Dad attended Jubilee school, which was 7 miles away from his home. He walked there and back. Eventually he was sent to live another family just so he could go to school without having to walk so far everyday. In those days, people sent children to live in other people’s houses in order to access school easier. In same way, children were hosted at my grandparent’s home. This was done without any payment. In fact, two of the students who stayed at my grandparent’s home, were the two people dad ended up doing busines with in London. One student was Muslim and the other student was Hindu. Dad remembers playing football a lot and was known for his footballing skills. Everyone always wanted him in their team when they played football. His aspiration was to play football. Another of Dad’s passions was catching pigeons, he was athletic and able to climb trees. He got the birds caught in the net.

He also said it was at school he learnt to smoke cigarettes and kept that habit until his late 50’s.

One or two years before the Partition, Dad remembers going with brother number 4 to a misseel. They went by boat which was owned by a Hindu villager. There were 50-60 others on the boat, all going to a demonstration/protest (in Bangla it’s called misseel) demanding for a Pakistan. They went to another town which was 15 miles away. Brother no. 6 was canvassing ‘door to door’ to persuade people to think to leave Assam (India) and become part of Pakistan. Soon after taking part in this misseel, brother no. 4 moved to Calcutta to work there as a tailor. He was there when the Calcutta riots happened in August 1946. To protect himself (to keep safe) he went and stayed with his/Dad’s cousin who was student at Calcutta University.”

‘Allah Megh De Pani De’, Abbass Uddin

“On Independence day, Dad, went without his family’s knowledge, with his friends, by boat to next town to celebrate. He was 15 years old. The only negative thing about independence was that Dad and his brothers weren’t happy about was the fact the British gave Karimgonj to India.

The Hindu student mention above, did not move out of Sunamgonj after Partition. However, many years later, they moved to Tripura (India). Dad didn’t see him for another 20 years, until he moved to London.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6MUPQTs5GsU

‘Nayer Badam Thooila De Bhai Allah Rasul Koiya’, Abdul Alim

West Pakistan days:

“Dad recalls, brother no. 4, returning from Calcutta in 1949 and brother no. 5 passing his metric exam and getting a job at CNB office in Sylhet. After three years, he moved to Dhaka to train as an estimator. Dad had left school and when not helping his older brothers, he would go and stay in Dhaka with brother no. 5. By mid 1950’s, brother no. 4 decided to come England. He arrived in London in 1958 and Dad followed his brother to London. Dad arrived in June at Gatwick airport and was received by his brother. He took him to East London by train. His brother rented out a room for Dad on Hanbury St. In his suitcase, he mainly had items other people gave to give to those already in London. Dad worked in Waterloo station in the café’s kitchen. After 8 months he moved to Smethick, Birmingham and worked in the steel plating factory. He never saw his dad again as he passed away. However, he was able to see my grandmother as he went back twice in the 1960’s. But when she died in 1967, Dad was in Birmingham and never saw her again. Initially he shared a room with 7 others, there were four beds in the room. They were either night shifts or day shifts. Those on day shifts would sleep in a bed during the night and those returning from night shift would sleep in the beds during the day. “

‘Oi Ekbar’, Joshim Uddin (sung by Abbass Uddin)

Demand for Independence

“By 1970, Dad was in London, having opened a restaurant in West London. He was supporter of breaking away from West Pakistan and attended Awami League meetings and hosted meetings at his restaurants and he was good friends with the president of the British Awami League.

Back in Bangladesh, during the Independence War, my grandparent’s home had a Bangladeshi flag up even though it was East Pakistan. The home was single storey and very long. 7 quarters for 7 brothers, however, only 4 of my uncles lived there with their wives and children. It was known as “Londoni Bari” (due to Dad and his brother being the only ones from the village being in London) and it had no immediate neighbours. The family was prosperous and very comfortable (financially). Unknown to my family, the freedom fighters had placed mines on the roads near Dad’s home, so when the Pakistan Army truck went over it, it would blow them up. When it did happen, they suspected Dad’s family and targeted “Londoni Bari”.

Soon after, one evening, trucks were heard approaching the family home; Dad’s brothers quickly got other brothers, wives and children up and left in boats from the rear of the premises. However, they were unable to get to brother no. 2 and his wife as the trucks nearly there and would have been caught. Uncle 2 and his wife were able to hide in the goat house, but the Pakistani Soldiers went through the home and outbuildings and found them. They started to beat him up, whilst they were doing this his wife saw a chance to escape and jumped into the waters and swam to the nearest house. After beating up Uncle no. 2, they threw him into the waters. He was able to swim to safety.

The Pakistanis, then, set fire to the house and all the outbuildings. They took some cattle for themselves and the remaining cattle and goats were locked in and the buildings were set alight. Some of the animals broke out, on fire and drowned in the water (other villagers saw this). When other villagers saw my grandparent’s place alight, they also left their homes and escaped, but their homes weren’t touched. Only our house was targeted. However, on different occasions, some of the village women were raped by the officers (not the foot soldiers), even the pregnant ladies were raped. These things were never spoken about until now (I knew the family history of the events during the independence war, but I never heard of the assaults and rapes the women faced, I thought it was other districts and perhaps my village was spared this).

My family lost everything. They had to stay with other relatives until it was rebuilt.

Uncle 5, had settled in Dhaka as he and Dad had purchased a house in Dhanmondhi. Uncle 5 lived there with his wife and two children. Uncle 5 was a prominent person in the area. Unlike some residents of Dhaka, they stayed there and did not return to village home. As the property was very big, and solid, other neighbours would come and sleep there during the night and would return to their homes in the morning.

As soon as the war was over, my dad went to Bangladesh to see his family and be with my mum.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EJphHoX5GvE

‘Loke Bole Bole Re’, Hason Raja (film version)

CIVIL LINES One Man’s Chronicle of Partition Kavita A. Jindal [i] ‘Rice fields are rice fields wherever they are.’ My youngest sister says this to console me. ‘Look how green the fields gleam under the noon sun here in Karnal, just like in Sheikhupura. The cows chew the cud the same. The milk is good, na?’ Lassi here does not taste the same. Pulao does not taste the same. It should, I know, it should be delicious, but my tongue has forgotten flavour. We are the lucky ones, the survivors. God has been good to us. We can regain in part, our material losses. I will never again see the lamp-post at the end of my street. The one I sulked under my whole youth. Where I sat alone to dream and to read my English books in peace. I will never again show my sons the land tilled by their forefathers; the two white houses of their childhood; quite the grandest homes in town. ‘Remove your cloak of sorrow,’ my sister says. ‘Life is yours to enjoy.’ I have to admit my father has taken the blow better than me. We will build again. He constructs new houses on empty plots of land. But my home is left behind. Here does not suffice. Not Karnal, not Delhi, not Bombay, nothing has the same fragrance, nothing tastes the same. Life has no flavour. [ii] I had a younger brother who was a simpleton, not right in the head. Didn’t understand the world, was difficult to control. He could be dangerous, unwitting. Once he dropped my baby daughter from the roof terrace like she was a toy. Miraculously, she was unhurt. That evening of genocide in late August 1947 we hid him with us in the fields. We crouched into new shoots hardly daring to breathe, praying that the Balochi soldiers (or mob, whatever you want to call the vigilantes, armies, and marauding bands of that time) would not discover us. My brother couldn't stay quiet. He didn’t understand. We pulled him down as he stood up in the dusk. We pinned his legs and arms. He shouted, he babbled. I whispered: ‘Shh. Shh. We’ll all be killed. Don’t you hear them baying for blood?’ Some of them our people, our neighbours, intent on spilling blood. ‘Why-y? Why-y?’ my brother called out like children do, and we couldn't quiet him. I risked a glance above the green stalks. A small gang, maybe eight men approached us, palms cupped to ears, listening on the wind to his whimpers. Stamping the crop as they advanced. We left him. My father and I. We left my brother. We slithered away on our chests, then crawled on hands and knees in the direction of a refugee camp. Surely from there they would take us to this invisible “border”, that we needed to find, get beyond, be on the other side of a line of demarcation freshly drawn on British paper. Clothes in shreds, mud in our mouths we tried to cross to what had become another country. It would be our “nation”. But in my mouth there was only the taste of mud. The mud of my fields. The imagined blood of my brother. We don’t know what happened to him. [iii] The women and children were summering in Simla. A neighbour there heard the news first. One white bungalow burned down. The other commandeered. (Later, it became the local jail!) Everything in the houses taken. ‘All gone, empty,’ the neighbour said. Though how could he know? He read my wife the day’s gazette. ‘10,000 non-Muslim civilians murdered. In one evening.’ Some were listed. My father’s name and mine. Recorded under ‘Killed’. Almost a month later in Simla my wife opened the door to me. I knew what it was to come back from the dead. I saw it in her eyes. Was I just an emaciated ghost? [iv] Were we naïve to believe, even ten days past Partition that our town wouldn’t turn on us? That the flames that licked at all hearts and all doors that month would spare us? I didn’t think everything would be consumed in the name of Freedom. In 1947 was everyone else insane or were we? Insane to believe we would be secure in our courtyard of privilege, wearing the turbans of our faith? Our ancestors had settled to farm and prosper. I had even counted back seven generations on the land, and seven generations ago we were Hindu before we became Sikh. How many faiths and saints had this fertile soil produced? How many kings and conquerors had renamed the place? We lived among believers who believed in numerous ways. A thousand ways to be Hindu. A hundred ways to follow Islam. Discreet believers of other sects, not fitting in with the diktats of temple, mosque, gurudwara, church. They all belonged in our town. We had myriad ways to pray and celebrate. Could I have known that we had myriad ways of viciousness and loathing simmering within us? That we were susceptible to politics, our leaders’ divisions, armies rising to respond to a call for the Sikhs who stayed put on their estates to be driven out. [v] The night of the mob there was one man who remained a beacon of humanity. To him we owe the chance of our new beginnings. ‘Bhagoo Nai’, our family barber, slipped into our house minutes ahead of the massacre-pack. ‘Flee. Now. Hide somewhere,’ he begged. Chittian kothiyan wale sardar will be attacked first. He’d heard this at the meeting as the soldiers prepared. Bhagoo put loyalty and humanity first. He was a musalman who risked himself, placing his real conscience ahead of tribesmanship. He was the reason we chose not to surrender to hatred. No matter what we heard and saw of what they did; and what we did; all those horrors each side had perpetrated; no matter how many wars are whipped up between old and new country, I cannot be harsh with others, on the basis of religion alone. And, no matter your chiding, I can’t help but mourn my real home where I won’t be able to return.

Chittian kothiyan wale sardar: the Sikhs of the white houses

Musalman: Muslim

On ‘Civil Lines – One Man’s Chronicle of Partition’.

This poem narrates the experience of India’s partition from the perspective of a young man forced to flee his home. It is based on my maternal grandfather’s account, that I heard as a teenager, in the 1980s. It took all these years to percolate and then to appear as a poem sequence in 2019. I also drew on stories that I heard from my mother. She was a baby at the time of Partition, in Simla with her mother, but the family narrative and collective memories were in her head. One of the things I explore in this sequence and also another poem about my grandfather, called ‘Outings with Daarji’, is the sense of sorrow about a lost homeland that gets transferred down the generations. Also the overwhelming silence of those who were most affected; they didn’t really speak about these events. As a granddaughter I pieced together the story from different accounts within the family. These poems are based on real events but lightly fictionalised.

Kavita A. Jindal

This poem sequence was published in the anthology ‘May We Borrow Your Country’ by The Whole Kahani, published by Linen Press in 2019: http://www.thewholekahani.com/may-we-borrow-your-country.html

Where are you from?

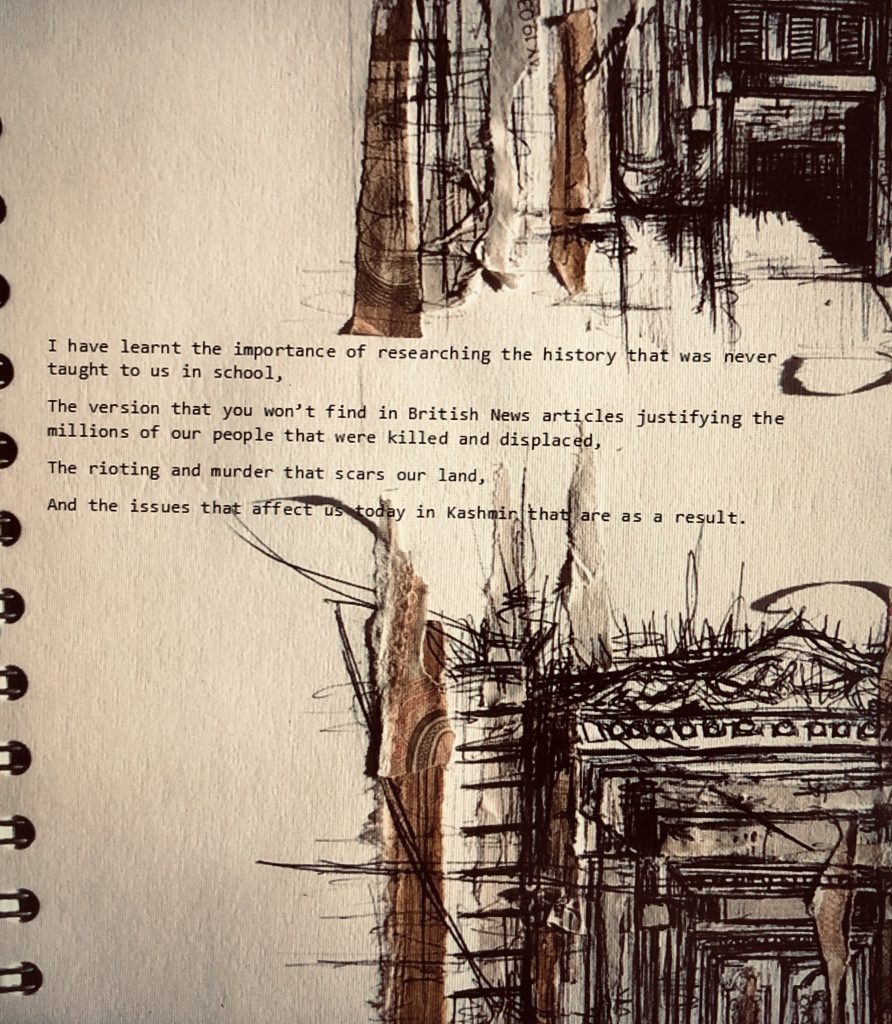

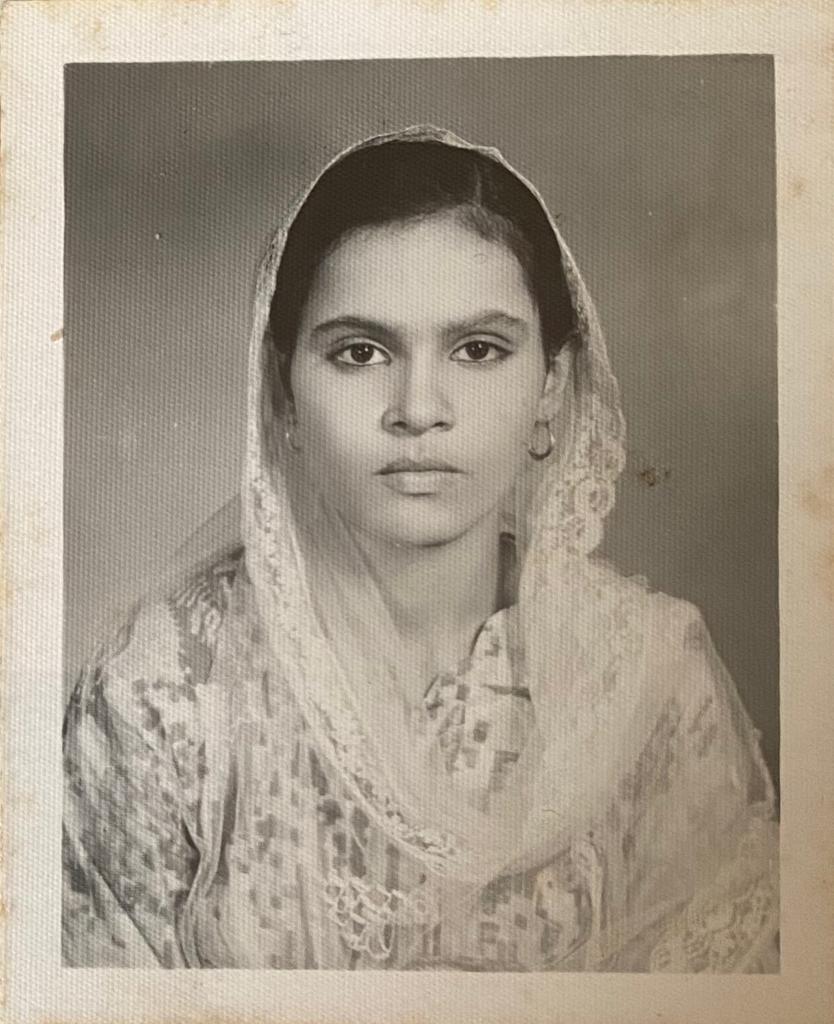

Mum and Dad just before they got married (they were engaged)

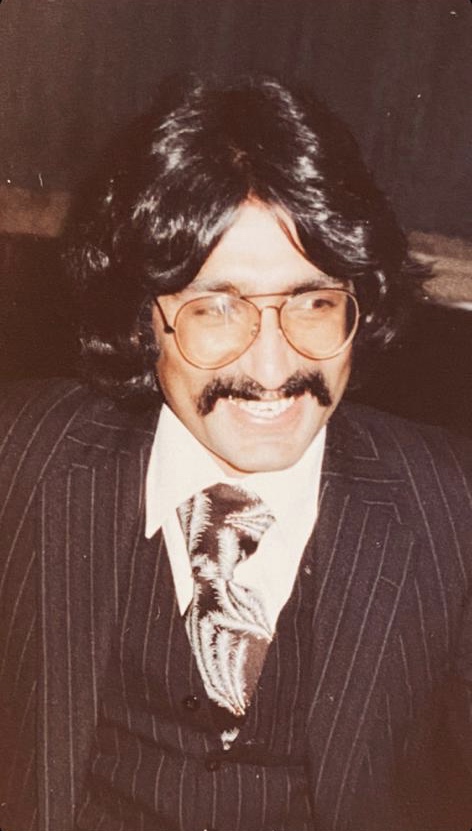

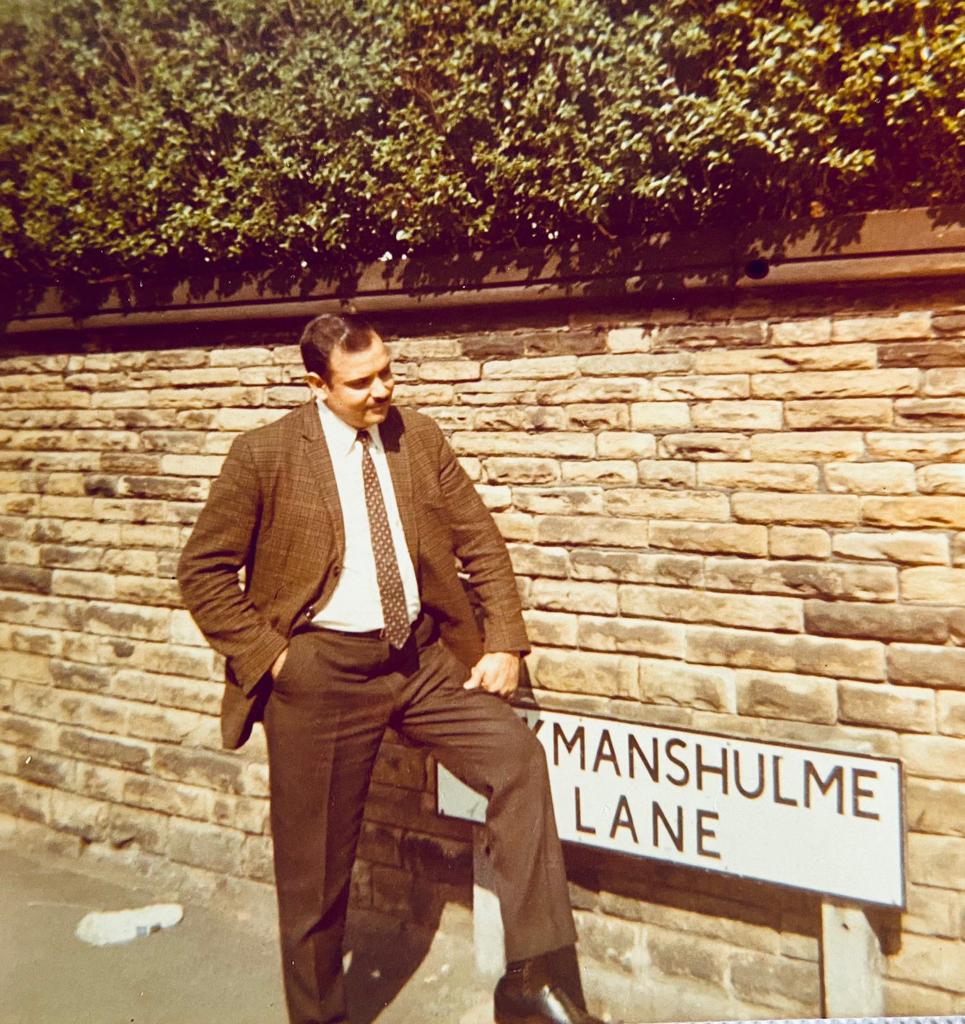

My Dad shortly after coming to England

Mum’s passport photo, before coming to England

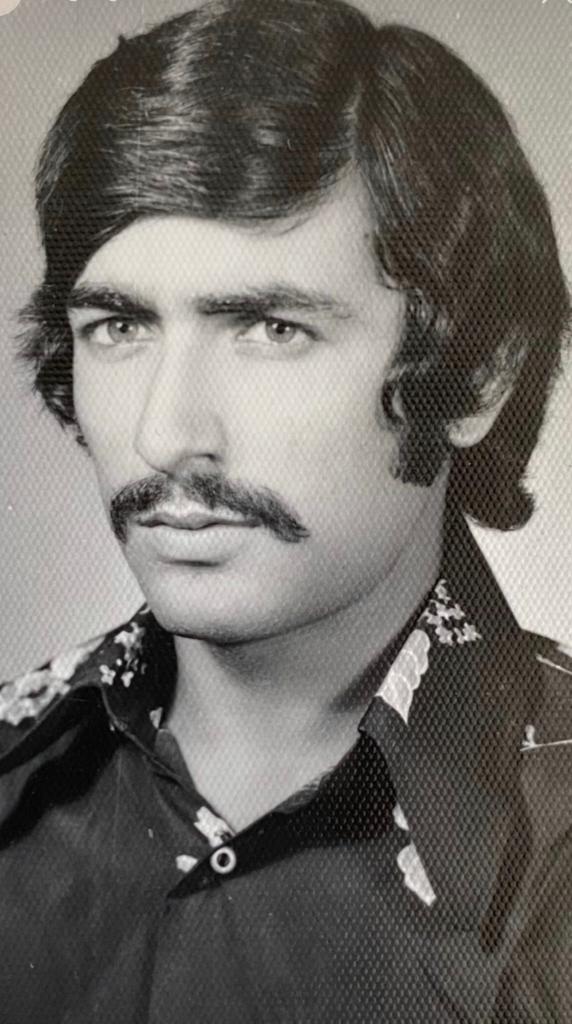

Daddy’s passport photo before coming to England

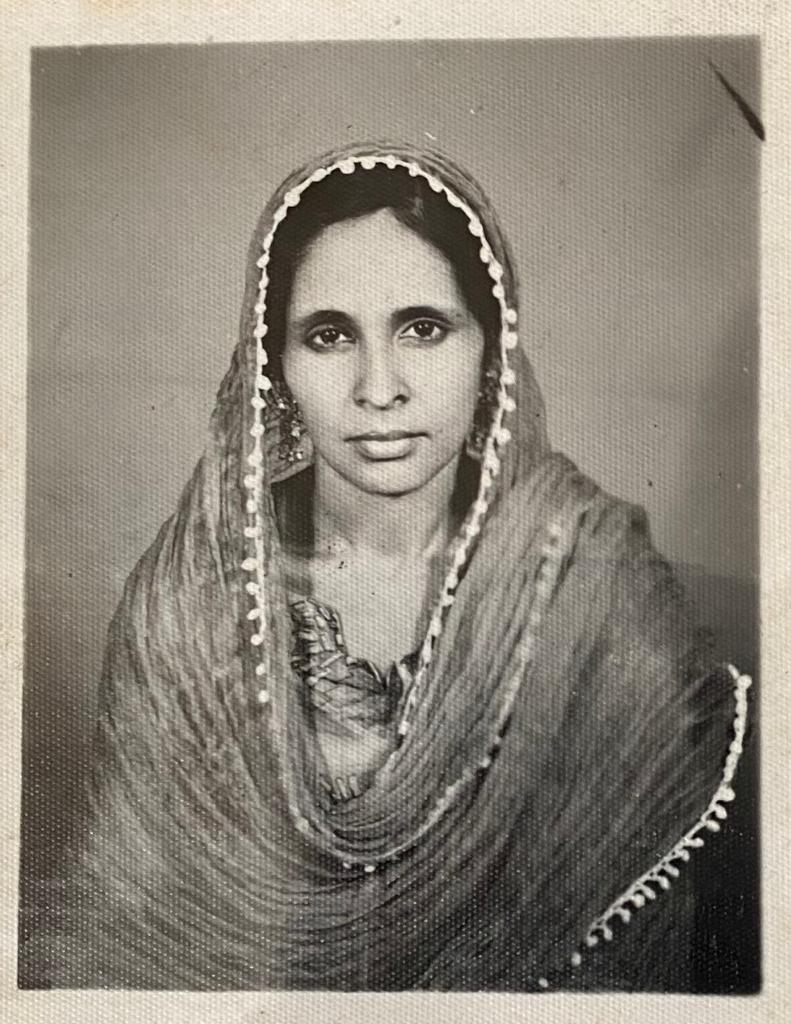

Grandma’s passport photo, before coming to England

Granddad when he came to England (Manchester)

Daddy before he came to England

Me in shalwar kameez

“Where are you from?” I get asked this all the time. I usually say “Huddersfield” or “West Yorkshire” or something along those lines.

Then the question “Where are you really from?”

I say “I was born in England” and then there’s a look of bemusement.

I ask “Do you mean what is my ethnic origin?”

“Ah yes Doctor. That’s what I meant”…Why does it matter where I am from? Or where my family are from? Does that make me any less of a Doctor to some of my patients? I hope it doesn’t but it does make me wonder if that’s what they are thinking. Hopefully they just ask out of interest. But unfortunately, I have had experiences where patients have refused to see me because of the colour of my skin. As Healthcare Professionals, we are taught to have no judgement against our patient’s beliefs; but is this one OK? That my naturally-bronzed hands cannot examine your pale skin, my brown ears may not hear your heartbeat in the way you want it to – even though I have a special interest in Cardiology and the white Doctor you asked to see instead of me is my junior.

Back to the intended question – my Dad was from Pakistan, my Mum too. Mum came to England as a school girl aged 14 with my grandparents and her siblings. They arrived in Manchester on the 28th July 1972 after a 20-day journey by road from Pakistan. Can you imagine doing that trip now? She has told me the tales of that adventurous voyage including eating all the different cuisines across Asia and Europe; her favourite memory of food on that journey was sitting and eating meat and naan-bread in Afghanistan with all the other travellers, talking about the possible ventures that lay ahead. Mum told me that it was mainly single men on that bus as not many people had brought their families with them at that time. Another memory that makes her smile is trying to buy breakfast in Bulgaria, no one understood each other so they made chicken noises to ask for some eggs to eat.

Mum started school in Manchester in September 1972 not knowing a single word of English. She went into her Year 9 class and a white girl kicked her in the legs for not understanding her. Mum came home crying. That abuse continued until eventually my grandfather decided to take her out of school and she started working as a Sewing Machinist at the age of 14. Her dream was to become a teacher but she never got the opportunity to do this. Now she’s been in England for 48 years, she’s done multiple training courses – I would say her English is probably better than mine but, whilst out and about, she still gets asked frequently if she understands what is being said to her.

Daddy was 22 when he came to England, it was 27th May 1979. We have video evidence of this stylish arrival. He was wearing a suit with bell-bottom trousers and a colourful round collar shirt. He had a mini-bus of family that went to London to collect him. Daddy already had 2 brothers living and working in Huddersfield. Until these 3 brothers started their own ‘Car Spares’ business Daddy started working in one of the wool mills in Huddersfield. I remember stories he told me about this time; including hiding to eat his food because people complained about the smell of curry. How ironic that now curry is seen as the national dish of England!

I’ve been thinking recently about what it means to me for my parents to be from South Asia and have made these journeys here from Pakistan. Thinking back further in time from when they arrived to stories of their own childhood. I was interested to find out if the people I know were aware of the creation of Pakistan. I asked some friends if they knew about the “partition of India” that happened in 1947. In simple terms; it was when Pakistan was established. Most of my (non-South Asian) friends did not know anything about this. My family were actually from India and were made to move to this new land “Pakistan”. This is where the Muslims were told to go. My family had to leave everything behind. I remember my grandmother telling me one particular memory of that time. They had what she described as a beautiful house, she was very house-proud; she said she particularly loved one certain dining set with plates and bowls with a stunning pattern, I wish I could remember what the pattern was. She is no longer alive for me to ask her. She told me she wanted to take this with her but she couldn’t; they had to leave everything and start this new life in this new land. No one knew where they were going, who they were going with or where they would live. She said she was one of the lucky ones because the family did not get separated from each other during this journey. When Daddy told these stories, unfortunately some people from his side of the family did get separated whilst traveling and staying in different camps on the journey. Thankfully, they were reunited later. These stories have formed part of my upbringing. They have made me learn that anything can be taken at any time. Why don’t people in the United Kingdom know about this partition? This mass migration. It was a decision made by the British – that might get some attention!

Anyway, the reason I began writing this was not to talk about history. This has been done before with much greater flair than I can achieve. I wanted to share a bit of my story; how I felt when I was younger despite being born in England. I would be embarrassed to wear Asian clothes. Sometimes, when I wore ‘shalwar kameez’ (shalwar – trousers, kameez – the top/dress) people would point and laugh at me. I remember asking my Mum to get me more “English clothes”. I understand now why they were upset by that. They never wanted me to lose my identity. Whenever anyone asked Daddy “Where is home for you?” he would always say “Pakistan”. Daddy passed away in 2011. I wish I could tell him I understand now why he always said that – even after many years living here in England. It was always the moon and star of Pakistan that would be displayed when the Cricket World Cup was on. I know now that home is where we feel the greatest sense of belonging. I think Daddy never really thought he belonged here. Even now if I go out in “shalwar kameez” I get treated differently. Most recently I’ve been asked “Do you speak English?!”. I have to say – I’ve also had some wonderful exchanges too; most prominently, friends being interested in South Asian culture and in the food. I have had some friends absolutely delighted at being invited to my wedding. There really is a spectrum of people in this world, isn’t there?

Daddy encouraged me to go to Medical School. He used to tell me becoming a Doctor would mean I can help people but he also used to say that if I ever needed to leave this country, it is a universal profession and I could take my skills anywhere; maybe he thought one day we might get asked to leave! I think about the challenges that were faced by all the South Asians that migrated across lands to their current homes. What power and bravery they have shown. I feel sad that these stories might be forgotten as we start to write our own stories here in England.

There are always reminders that I am ‘different’ but my concerns are not how I look, but the health inequalities I have seen. As a female Doctor with South Asian heritage, it disheartens me that our South Asian community have a much higher rate of non-attendance to cancer screening; that South Asians are less likely to seek help for mental health conditions – a white person is twice as likely to be getting help for their mental health disorder; our huge risk of Heart Disease and Diabetes. I am one of the many Doctors who are trying to raise awareness of these issues. I hope we can make a difference.

I’m proud of being British but I’m also proud of my heritage. I’m proud of my family for coming to this country with nothing and building a life here. I am proud of my grandmother for leaving her beautiful crockery; I am proud of my mother for accepting the racism she faced and not letting it control her life; I am proud of Daddy for showing me that with hard work and determination anything is achievable, that if I just concentrate on myself, and not the people around me, I can succeed.

Daddy was able to attend my graduation from Medical School in 2010. But I feel he never really got to see me building my life around the lessons that he taught me. I’m not embarrassed to wear ‘shalwar kameez’ anymore, I am glad I learnt Urdu, it means I have good communication with my family that reside in Pakistan. It means I can speak to older South Asian patients here in England with words that make them feel at home.

So, where am I from?

I am from Huddersfield in West Yorkshire.

What is my origin?

Pakistan and India.

Where is home for you?

Home is England in Summer 2008. I was with my parents and brother; back from University in between my 3rd and 4th year of Medical School and it was just before we found out about Daddy’s diagnosis of cancer. This is the time in my life I felt the greatest sense of belonging.”

Dr Henna Anwar

BSc(Hons) MMedSci MBChB

GPST3 Pennine Scheme

Former Medical Registrar after completion of Core Medical Training

(before change to Accreditation of Transferable Competencies (ACTF) pathway GP training).

Radio Sangam Presenter: Doctor Henna’s Ladies Hour Sundays 10-11am.

Instagram: @doctor.henna

Twitter: HennaAnwar

This contribution to the collection consists of a contributor’s mother’s memories of her childhood in East Pakistan, the Bangladesh Liberation War and her migration to the UK. The contributor’s mother also remembers the songs she used listened to: she loved the songs from the Bengali film, Rupban and the songs of Abdul Karim, Abdul Matin and Lalon Shah.

“Mother was the youngest of 3 children; she is from Sunamgonj, North of Bangladesh. She lived a very comfortable life, in the only brick-built house in that area. It was surrounded by lush bamboo jungle, various tropical trees, and thee large ponds. She recalls as a child, being told there were tigers in the jungle, although she never saw one, she did see deer in the jungle behind her home. She saw dolphins in the Surma River as a child. Her father had a gramophone and people would come from far villages to hear songs being played on the gramophone. Both of Mum’s parents came from well-established families and were quite well off. She was free to do whatever she wanted and this was mostly climbing trees and drawing. She was quite spoiled especially by her one paternal uncle who worked for the Forestry Department. Her marriage was organised by her paternal aunt who recommended my father to my grandfather for his honesty and for being a good person. When my grandfather found out my father lived in London, he said no, but his sister persuaded him that this would be a good match. So, when other got married, she was thrown into the deep end as she didn’t know how to cook or how to wear sari. Her parents’ home always had maids, cooks and workers. When my mother went to her marital home, her father sent a cook and personal maid with her, as mum had no “home skills”. She said she was petrified to move to such a home that had so many families living jointly. As the wife of the second youngest brother, she was at the bottom of the pecking order and would be expected to do the lesser tasks. Once she was asked to cook rice, she put too much rice in a pot and burnt it. She said that the other wives made fun of her and her higher background. The cook and maid her father provided for her were sent back by elder brother in law, so as not to create animosity between the sisters in laws, so she couldn’t ask them to do the tasks.

She soon moved to Dhaka, much to her relief, and lived in the house my dad and his brother bought together. My dad came back to UK and she lived in Dhaka with her brother in law and his family. Mum had two cousins older than her, who lived in Dhaka and worked in a bank, so they would always visit and check on her as well as treat her.

One week before the liberation war started, her brother in law told her to go back to Sunamgonj for her safety. She took the train to Sylhet and then bus to Sunamgonj. First, she went to my father’s village but her father came and took her to back to his home. Sometime later, she was sent to her maternal grandmother’s home. It was further away and less likely to have Pakistani soldiers go there. Even Mum’s paternal gran, paternal aunt and her children went to live there too. This was a lot pressure for my mum’s maternal grandmother as it impacted on food, fuel, bathroom use and space. Mum said even her middle sister came with her 4 children but her grandmother told her to go back to her husbands as they had no space.

In the meantime, my grandfather (Mum’s dad), remained in his home with the workers to make sure the house, crops and cattle was protected. His home was across the Surma river and you would need a boat to cross the river so Pakistani soldiers would not go to that side. However, they would fire shots from time to time. One occasion, my grandfather sent his worker on an errand near the river, he was shot and killed. The Pakistani soldiers would hangout drinking tea or smoke in the small stores near the river; to carry favour with the soldiers, one of the shop keepers told them my grandfather supported Independence. He took them to my grandfather’s house. The Pakistanis ransacked my grandparents’ home, they broke open all the almaris (locked metal wardrobe), took all the expensive belongings, took all the rice, cattle, poultry and took it away by boat. They grabbed my grandfather and spoke to him in Urdu. He pretended not to understand, so the shop keeper came to explain. He said they are going to take him to the PT school and shoot him. Then he whispered to him; “give them money”. My grandfather told his worker to go to his sister and get as much money as he can, but only to give the money to the soldiers not the shopkeeper as he believed he would keep it for himself. Grandfather’s worker was able to get to the school in time and pay the soldiers not to shoot my grandfather. Grandfather went back to his home to secure it and then went and stayed at his in laws, where my mother was.

It was whilst at my mother’s grandmother’s place, at 1 am in the morning they heard on the radio that Londoni bari (my father’s home) was burnt down. To receive the radio service, my mother’s uncle would climb a tree to get a signal. The radio service was broadcast from Calcutta and read out names of homes burned or damaged by the Pakistanis. Everyone in my mum’s family was shocked and later found out the exact details but were not able to help as they were already helping so many people. Mum stayed at least 5-6 months there. In England, Dad had applied for Mum to join him, but there were problems and had to wait after the war ended. When the war ended, Bangladesh’s first ever foreign minister, who was my father’s uncle as well a close friend of my uncle number 5, helped my mum get her visa to UK, so she could join Dad. Whenever he came to UK, my father would always go and see him.

My mum said after things settled down after the war, they returned to her parents’ place and was very upset at the damage the Pakistan army caused. She helped tidy it up and get the house back into order. Pakistani soldiers stole all the expensive stuff or things that could be sold for money. After some time, she went to her marital home and from there, she was told to come to Dhaka, she was not aware that she would be going for an interview for the visa. Because of Dad’s uncle, she got her entry to UK very easily. She went back to Sunamgonj to say goodbye to her family. She said her heart broke to leave her family behind, especially her father. She came by BA and landed in Gatwick in 1972. My mother said London wasn’t as green as she had been told it was and she was shocked that her home had no internal bathroom and had to use public baths. After complaining to my father for a couple of weeks, an internal bathroom was fitted. She said she had to stop herself looking at West Indian people as she had never seen black people and she had hoped that there would be more Bengali people there, but there wasn’t. She said she eagerly looked forward to receiving letters from her father and every 3-4 months she would speak to her father as he would have to go to the town to receive a call from her. After having two children, she joined an English class at the local church and learnt English with the hopes of continuing on to further education. She had also learnt how to cook. She was in a privileged position to be able to go back to the newly formed Bangladesh every 2-3 years and would stay in Bangladesh for 3-6 months before returning to London.”

All rights reserved. These contributions have been published as part of this online exhibition with permission by the copyright holders. If you are unhappy with the publication of any of these pieces, please contact j.hornabrook@lboro.ac.uk